Below an article on P’ng Chye Khim and his school from the martial art magazine ‘Combat Magazine’ ( August 1991).

Below an article on P’ng Chye Khim and his school from the martial art magazine ‘Combat Magazine’ ( August 1991).

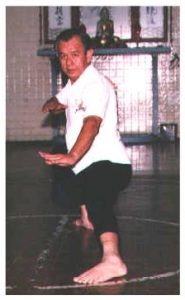

Master P’ng Chye Khim is a native of Penang, an island Province situated off the west coast of Peninsula Malaysia. He was born in 1939 and during the earlier part of his life studied a number of Chinese Wu Whu systems. At the age of 19 Master P’ng met a monk from the Southern Sao Lim temple in Quanzhou, a city within Fujian which is approximately two hundred miles south of the provincial capital. His name was Shi Gao Sen, and as well as being a monk he was a Master of Sao Lim Quan. Master Shi taught a system called Hood Khar Pai, one of the countless variations upon the Sao Lim theme which exists today, owing to the the terrific spread of this art not only within China, but the intire Asian Circle.

Master P’ng Chye Khim is a native of Penang, an island Province situated off the west coast of Peninsula Malaysia. He was born in 1939 and during the earlier part of his life studied a number of Chinese Wu Whu systems. At the age of 19 Master P’ng met a monk from the Southern Sao Lim temple in Quanzhou, a city within Fujian which is approximately two hundred miles south of the provincial capital. His name was Shi Gao Sen, and as well as being a monk he was a Master of Sao Lim Quan. Master Shi taught a system called Hood Khar Pai, one of the countless variations upon the Sao Lim theme which exists today, owing to the the terrific spread of this art not only within China, but the intire Asian Circle.

As a student under Master Shi, Mr. P’ng was embarking upon an apprenticeship which was not only include the study of Sao Lim Quan, but Bagua Zhang and Hsing-I Quan, two of the most noted ‘internal fist’ arts of which this monk was also a Master.

As a student under Master Shi, Mr. P’ng was embarking upon an apprenticeship which was not only include the study of Sao Lim Quan, but Bagua Zhang and Hsing-I Quan, two of the most noted ‘internal fist’ arts of which this monk was also a Master.

At this early stage I would like to clarify the meaning of ‘Sao Lim’. As Penang is Chinese community which speaks by the way of the ‘Hokkien” dialect (a southern Chinese variation which originates from within Fujian). Master P’ng retains the use of Hokkien at his school. By way of further clarification the word(s) Shao Lin originate from the Mandarin language which is used to the north of China, within the capital city of Beijing and surrounding provinces.

Prior to my interview with Master P’ng I watched the night-time session as it grew from a mere class of two through to its highest number which was six. Intermittently the students would drift in, with each one observing the same order of events. First, the respectful salutation to the painting of Pu Ti Ta Mo, the legendary founder of Sao Lim Ssu, and then the regimental pounding of the hands upon the rough cylindrical stone tablet. After approximately two minutes the hands would then be rubbed with an herbal based ointment specifically prepared to remedy any ill effects as may be experienced from such austere hand conditioning.

Knowing that Master Higaonna had visited this school I asked Master P’ng about this hand tonic as I was quite certain that Higaonna Sensei was using a similar motion. Master P’ng replied that this was, indeed, the same liniment that Master Higaonna was using or, at least, had purchased from his school. Indeed, it was this liquid that Master Higaonna can be seen administering on the BBC documentary ‘The way of the Warrior’.

As the students would be applying this brown and rather pungent smelling healer after every encounter with the stone tablet I asked Master P’ng just how long a bottle of this ointment would last, assuming that the student works out every day. The answer to this was that one bottle which contains 125 ml of curing agent would last about one week.

Tia Sha Jian

For more than 10 years now, many so-called martial artists have enjoyed ridiculing a certain practice within traditional Chinese Wu Shu (Martial Arts) called the, ‘Iron Palm’. Seeing this as being no more than a flowery fabrication or gross distortion of the truth, it has never really been taken seriously as one might have hoped, even to this day. This I personally find quite incredible seeing as the international acclaimed master of Okinawan Goju-ryu, Sensei Higaonna Morio has been preserving this technique for at least the past decades. Not that Master Higaonna refers to it as such – for him it simply serves as part of his daily workout. But within Hood Kar Pai this aspect of training goes by the name of ‘Tia sha Jian’ which literally translates as ‘Iron Sand Palm’, a technique whose earliest traceable record dates back to the ‘I Chin Ching’ (or ‘Muscle Chane Classic), a document which first appeared within the Central Sao Lim Monastery of Honan Province.

Unlike the ‘makiwara’ practice of karate-do, where emphasis is placed upon the development of callouses upon the forefinger en middle finger knuckles of the hands, ‘Jia Sha Jian’ conditions all four knuckles of the hand, and in such a way that the knuckles do not, in any way, appear ‘ugly’ – like mine! (I feel that Master P’ng enjoyed telling me that!).

Unlike the ‘makiwara’ practice of karate-do, where emphasis is placed upon the development of callouses upon the forefinger en middle finger knuckles of the hands, ‘Jia Sha Jian’ conditions all four knuckles of the hand, and in such a way that the knuckles do not, in any way, appear ‘ugly’ – like mine! (I feel that Master P’ng enjoyed telling me that!).

And lastly, I would like to make it clear that ‘Iron Palm’ training is a technique that not limits itself to training merely the palm – all of the hand undergoes this conditioning. Indeed, many practitioners of Wu Shu practice just the one hand, the reason being that once the student has learnt and understood the process for this development he can, if he so wishes, go on to train other parts of his body in the same manner. Whether is be his other hand, his elbow, his foot, or even his head! Traditional Sao Lim training stipulates that ‘after basic training energy is reserved for training the hand’. However, common practice within this particular Sao Lim school sees a reversal of this attitude. Here we see that the entire training session revolves around this practice, with the development of ‘forms’ and other health-generating exercises serving as lengthy breaks in between such full-on hand strengthening exercises.

‘Pushing – Hands’

‘Pushing – Hands’

Upon the floor I noticed two white circles, one inside the other. As I had expected, these circles were combat zones, the inner circle representing the commencement area of the dual whilst the outer ring dictated the boundary outside of which had to force the opponent in order to win.

Within traditional Okinawan Goju-ryu we have an exercise called ‘kaki-e’ which is a two man drill fashioned after the Chinese exercise known as ’tui-shou’, or ‘pushing hands’. With both of these exercises the two opponents stand opposite each other, almost nose-to-nose whilst certainly wrist-to-wrist, and whereby upon commencement of the exercise both combatants attempt to force the other either into submission or out of the designated area. At this point I was rather eager to discover whether Hood Khar Pai posses an exercise called ‘kaki-e’ but, alas, I was sadly disappointed. In fact nothing even came close. however, I did learn that they practiced an almost identical drill, the only difference being that there was no real restriction upon how to defeat your opponent; short of giving him a punch on the nose you were quite at liberty to employ just about any technique you desired, whether it be a lock, throw, destabilization, or ‘push’ not dissimilar to the ‘pushes’ (or ‘slaps’) which are so much a part of the Japanese sport of ‘Sumo’.

The age group represented by evening’s class ranged between the mid twenties to the upper fifties. Younger students did attend, and these included children who are permitted to train from their early teens. However, as far as seniority within the school was concerned the senior students would always be gauged by the number of years that the student had been training within the school and not by the students actual age.

At this point I inquired as to the obvious lack of female students within the school, to which the Master replied that he did not permit ladies to train. Not, he hastened to add, for reasons of discrimination. Moreover, it had been his experience that females just did not cope so well with this style. Again, not that he had ever had to ask a female to leave as it had always been the student who would first call it day, moving on to find a less arduous form. Thus, any females who now express a desire to train, Master P’ng automatically steers in the direction of the nearest Taiji school or Karate ‘dojo’, of which Georgetown, the principal area of suburbia within Penang, boast quite a healthy number.

Forms Within Hood Khar Pai

Forms Within Hood Khar Pai

Hood Khar Pai contains what I consider to be a staggering fifty forms!! Thirty of these exist as empty handed ‘solo’ patterns, with a further ten practiced as two man (or partnered) drills, whilst the remainder prevail as weapons forms.

This evening I saw a total of eight, beginning with three of the novice patterns. These employed extremely low ‘shiko’ and ‘zenkutsu’ type stances whilst the ratio of open handed:closed handed was an approximate 50:50, with emphasis placed upon elbow strikes. Although serving as novice forms these did contain some rather tricky maneuvers, including 180 degree and even 360 degree leg sweeps which were scribed as arcs upon the floor.

The corkscrew punch (which I was assured, is of Chinese origin) played a rather significant role within these forms, however, having questioning the Master upon this I learnt that this technique was an introduction to the pattern on behalf of the practicing student; it did not constitute any part of the Hood Khar Pai system and would be eradicated at a more critical point from the individual’s practice.

The corkscrew punch (which I was assured, is of Chinese origin) played a rather significant role within these forms, however, having questioning the Master upon this I learnt that this technique was an introduction to the pattern on behalf of the practicing student; it did not constitute any part of the Hood Khar Pai system and would be eradicated at a more critical point from the individual’s practice.

Of the more advanced solo forms I saw a number of forward and backward somersaults, together with jumps, spins, and high level kicks. As far as the open handed techniques were concerned, these concentrated upon strikes utilizing the palm heel, the spear hand and the crane’s beak, whilst the closed hand techniques focused upon extensive use of the reverse punch and the back knuckle strike.

What I had seen of the solo forms had impressed me. In particular the low, classical, crouching postures (such as the ‘ko-kutsu’ stance) which are so indicative of the Southern Chinese styles of Wu Shu. However, none of the two man drills had been demonstrated this evening. But of the weapons forms I had observed three patterns employing the Bo stave, ( a, solid, wooden pole approximately two meters in length) followed by another which utilized the tufted, single bladed spear, and then one final pattern demonstrating the use of the Broad sword. All very exciting to watch.

Having worn themselves out through vigorous repetitions of ‘forms?the students will often rest a while, replenishing their bodies with an interesting concoction of herbal tea. Quite unlike the watery brew for we british are renown, this blend is almost vicious in its’s consistency ?but by no means unpleasant. As they drink they are either seated upon the floor or, perhaps the large stone slab which rests to one side of the training hall. Meanwhile, as they talk they SLAM their faces, their palms, their knife hands and the back of their hands into the cold gray rock upon which they are seated.

Many of the Southern Chinese Wu Shu systems contain a solo form known a ‘Sanchin? This I know for a fact. Therefore, I was stopped dead in my tracks when I discovered that no such pattern existed within Hood Khar Pai. However, wind was immediately restored to my sail upon learning that Hood Khar Pai does posses a ‘form’ known as ‘Pai Herk Quan’, or ‘White Crane Fist’. Two years ago Master Higaonna revealed that the Southern Chinese White Crane Boxing System had quite a bearing upon Okinawan Gojo-Ryu-Karate-Do, and so now I was quite interested to see how the Southern White Crane had influenced this particular system of Southern Sao Lim. According to Master P’ng, this form, together with ‘Er shi Mai’ (Plum Blossom Form), ‘Lui It’, and ‘Qui Chien’ (two other forms which have no real translation into English) present a rather accurate overall impression of this style.

‘Hard’ or ‘Soft’?

Being neither an ‘internal;’ nor an ‘external’ system, as such, Sao Lim does appear to include two of the most extreme attitudes pertinent to both of these schools od practice. From the ‘internal’ schools Sao Lim had assimilated practices which fuse both Ch’an mediation (as introduced to the Northern Sao Lim Monastery by Pu Ti Ta Mo) together with ‘chi-gung’ type practices, although Sao Lim does not define these as such. Conversely, Sao Lim also places great emphasis upon the ultimate in ‘external’ training – the aforementioned, ‘Iron Palm’.

So where, in view of all this, do Hood Khar Pai’s loyalties lie? Within the ‘internal’ systems of Wu Shu or within the ‘external’ systems? In answering this question Master P’ng related to a situation illustrating a strategy from self defense: given that you have been attacked by way of a body punch the Hood Khar Pai student may intercept the attack by way of an open handed ‘internal’ deflection. Should this defense warrant an aggressive counter this may very well take the form of a strike with the conditioned palm heel towards the attacker ’s midsection. Now, appearing to be an ‘external’ response this technique would be deflected in conjunction with a short bust of energy from within the ’tan tien’ region of the lower abdomen, which is where one’s ch’i power is stored. Thus we see both the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ practices at work within the same action. As Master P’ng sees it, there comes a point within one’s martial arts training were body and mind through the use of ‘internal’ and ‘external’ practices cease to be two elements working in harmony. To Master P’ng’s mind they ARE one.

Compared to the regimental and fanatical ways of the staunch, Japanese influenced karate ‘dojo’, training the Chinese is very much a relaxed affair. Here, the emphasis is upon self training, with assistance or guidance from the senior students when and where necessary. Whereas the training is hard it is not, perhaps, continuous. In other words, training is as tough as the individual cares to make it.

In the case of this particular Sao Lim school, Master P’ng, who is a qualified Acupuncturist and Orthopedist, has his clinic to attend to whilst his students train themselves in the rooms to the back. Master P’ng joins his students only after the last patient had been attended to and so very often personal instruction from the Master will not occur until very late into the night. Thus, to a large degree, the teachings of Master P’ng exist more upon the corrective and technical levels of instruction.

Void of such masochistic tendencies as typically reflected by other Oriental disciplines, the practice of Hood Khar Pai, as with many other Wu Shu systems, moves at the individual ’s pace knowing full well that as a life long practice there is no real urgency – no real hurry. To him the martial arts are a way of life, not a way of death. And as Master Higaonna once said, the martial arts are designed to be Constructive as opposed to Destructive.

The School Of Master P’ng

The School Of Master P’ng

The ‘Penang Sao Lim Athletic Association’ compromises of three rooms and a large training hall. As you first walk into the school from the street you pass through an outer room which takes you into an outer room which then takes you into the main training hall. In front of this hall and off to one side in the Master’s office, which also serves as his Consultation Room. Finally, to the very back of the training area is another room, into which I never stepped. Here, I am told, are a number of training bags together with other hand conditioning devices.

Within the Main Hall, itself, are a number a number of training bags, each with it’s own density and each with a specific purpose for training. Meanwhile, affixed to both the left hand and the right hand walls are two large blue sponge type surfaces which are further aids for developing power and penetration, both with one’s punches and with one’s kicks. Lurking within the shadows somewhat unassumingly stands a ‘Wooden Dummy’, the awesome looking training device which is synonymous with ‘Wing Chun’ training, thanks to the exposure from bygone years of the Bruce Lee era. Incidentally, ‘Wing Chun’ is another Fujian based style of ‘Southern style’ Wu Shu reported to have its origins within the Quangzhou temple.

Positioned high upon both walls are a number of photographs which are the the portraits of previous Masters and exponents of Hood Khar Pai. These line both sides of the training hall and lead to the far end where there stands a small shrine with a painting of the founder of Sao Lim Boxing, the venerable Indian Monk, Pu Ti Ta Mo. Preceding these portraits are a number of smaller photographs which illustrate some of the movements from this system as well as snap shots taken at various demonstrations. Many of these include breaking techniques, illustrating the ‘internal’ powers through the development of ‘chi’ and the ‘external’ powers achieved through conditioning.

Finally, then, I take a brief moment to speak of Master P’ng Chye Khims’s office, for which this room hang two large pictures. One shows the distinguished Martial Arts Historian Mr. Donn F. Draeger, who was a very good friend of Master P’ng, whilst the other shows a Master Hayakawa Sooho, the highly acclaimed Aikido Sensei. A number of years ago Sensei Hayakawa formed his own branch of Aikido which he has named ‘Wado’, the ‘way of peace’ which is not to be confused with Master Ohtsuka’s karate style of the same name. This high ranking Aikido teacher is also a very honored friend of Master P’ng. Master P’ng’s school, ‘The Penang Sao Lim Athletic Association’ is a most humble one. Earlier this year Master P’ng traveled from his homeland and across to France in order to attend a national Festival of Martial Arts. There he was received both as an honored guest and an instructor for the Chinese ‘aspect’ of the program.

Next year it is hoped that Master P’ng will be visiting this country in an attempt to share with us his inexhaustible knowledge of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts. As a matter a fact, 1992 promises to be a most rewarding year from a Martial Art viewpoint, and with Master P’ng gracing our shores this would most certainly add further dimension.

N.B. For those readers who cannot afford the airfare nor wait until Master P’ng flies in, I should like to recommend the book, ‘SHAOLIN: An introduction to Lohan fighting techniques’. Published by Charles E. Tuttle Company Inc. this book was first released in 1979. The authors are Mr. Donn F. Draeger and Master P’ng Chye Khim. It is a hardback book and should cost in the region of ten sterling pounds.